Beatrice Wood: the Alchemist & California-Cult Artist Turning Mothballs into Gold

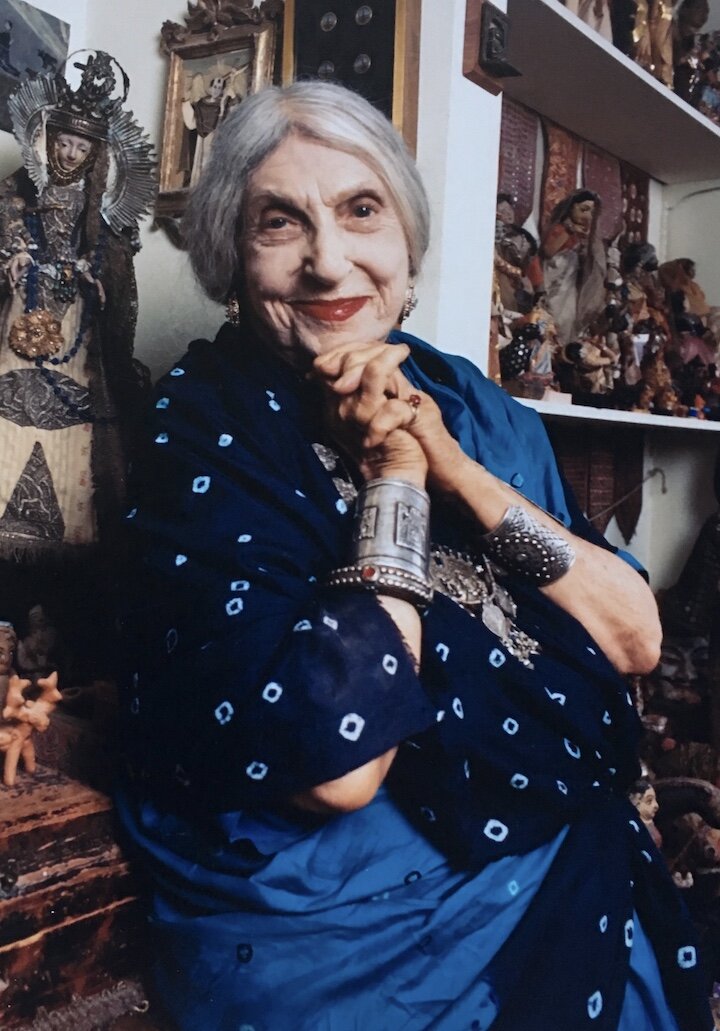

Beatrice Wood, Courtesy of Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts / Happy Valley Foundation

Beatrice Wood was one of the rare, female artists more successful in her later years than ever before in her life. A woman who seemingly defied time, she lived to be 105 years old famously attributing her longevity to “chocolate, art books, and young men.” Best known for her magnificent, luster glaze ceramics and sometimes provocative personality, Wood was a key member of New York’s Dada movement during the early 20th century and continued to create a reputation for herself as an artist after moving to California in the 1920s. She was declared a "California Living Treasure” by Governor Pete Wilson and an "Esteemed American Artist” by the Smithsonian Institute just a few years before her death in 1998.

While her connection to the Dada movement and to influential figures like Marcel Duchamp and collectors Louise and Walter Arensberg have been explored at length, there hasn’t been much discussion about the artist with regard to her interest and study of Theosophy.

Theosophy, a philosophy known for bringing the mystical teachings of Buddhism and Hinduism to the West, played a key role in the development of early abstraction in Europe through its effect on artists like Hilma af Klint, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Piet Mondrian, and likewise, no doubt influenced the life and work of Beatrice Wood as well. While the connection between Theosophy and art has historically been downplayed by critics and historians alike, there is a great deal we can learn about the artist and her work by framing it in context of her Theosophical beliefs.

Beatrice Wood with fellow Theosophist Dora van Gelder Kunz, 1925, Courtesy of Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts / Happy Valley Foundation

A movement which gained momentum due to the increasing rigidity of Christian doctrine and rise of secularization during the end of the 19th century, Theosophy sought to recover an ancient wisdom that reunited scientific and spiritual thought. Founder Helena P. Blavatsky believed that the development of a new civilization with greatly attuned psychic and spiritual potential was already being born in the United States and there was speculation that this would most probably take root in California. The early Theosophists settled in Hollywood in 1912 and built a center for the study of Theosophy called Krotona. When Hollywood became a burgeoning center for film and entertainment in Los Angeles, the peace-loving Theosophists eventually re-located their center to nearby Ojai in 1926.

Annie Besant and Jiddu Krishnamurti, Photo courtesy of Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts / Happy Valley Foundation

Wood’s study of Theosophy and the teachings of Jiddu Krishnamurti, an Indian brought into the Society as one of the great future world leaders, directed a large part of her life beginning in the early 1920s. Having grown up in an upper class family of New York with a childhood she felt quite constricting, Wood rebelled against the confines of high society in search for a deeper meaning of life. In her quest for happiness, she turned to the study of the esoteric teachings of spiritual enlightenment that Theosophy offered, particularly in the form of texts written by prominent Theosophists Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater.

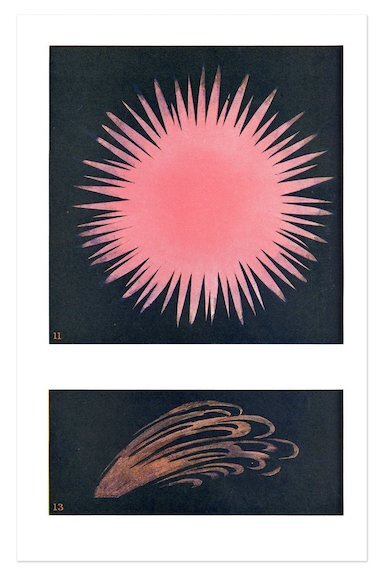

One of such books included Thought Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation, which introduced the idea of a spiritual and visual component to understanding thoughts and feelings. In this book, Besant and Leadbeater describe how the human aura changes in size, form and color depending on an individual’s emotional and mental state with certain “thought forms” correlating to different colors and shapes. Bright hues were preferable over muddied or dull colors. In fact, the more brilliant and pure a color, the closer the individual was to spiritual enlightenment. For example, a feeling of “vague pure affection” resembles a cloud of brilliant pink, but when the feeling becomes self-centered into “vague selfish affection,” the color is inherently muddied, reflecting a “dull hard brown-grey of selfishness" showing itself “very decidingly among the carmine of love.”

Thought Forms reflecting 11). “Radiating affection” and 13). “Grasping animal affection” as illustrated in Thought Forms published in 1901

A discovery of an article Wood wrote for The Star, entitled “Color, Light, and Art” demonstrates that her predilection for radiant luster glazes may have been influenced by her study of Theosophical color theory. In her article she writes, “as a person evolves, he desires fresher, clearer colors, for they are a reflection on the physical plane of what is taking place on the inner planes. Leadbeater explains in Man Visible and Invisible (1903) that the colors in the aura of a highly developed man are translucent, pure, and radiant, and those of the lowly developed man are muddy, dark and ‘dirty’ in hue.”

“Translucent, pure, and radiant” are words which also perfectly describe Wood’s luster-glazed vessels. A luster glaze is a fired, glass-like surface on a clay body, where metallic salts on the glaze’s surface give it an iridescent appearance. Wood achieved these brilliant luster glazes through reduction firing which requires the absorption of oxygen from both clay and glaze.

Photo: Beatrice Wood, Luster Chalice with 10 Handles, 1982, ceramic, 13”h x 7.5”dia, Permanent Collection: Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts / Happy Valley Foundation

Just as the Theosophical texts advocate for a sort of spiritual cleansing through purification of color, Wood’s life-long study of techniques in luster glazing reflect a similar dedication to a mastery of brilliance. Her luster-glazed vessels in their radiant hues reflecting not only gold but bright purples, pinks, and blues upon closer examination, evoke a sense of alchemical perfection, demanding a kind of reverence only reserved for the sacred and otherworldly. Wood’s extraordinary sense of light and color become even more magnificent as her work is handled and examined— changing colors as the light moves and refracts from the vessel in different ways.

Beatrice Wood, Blue Luster Bottle with Three Masks, Permanent Collection: Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts / Happy Valley Foundation

This purification, not only achieved through her mastery of luster glazes, but that undergone inside the kiln, where vessels quite literally undergo a kind of transmutation and burning away of the non-essential (she was known to throw various chemicals including mothballs inside the kiln to influence the effects of firing), can also be seen as a metaphor for the type of spiritual purification likely espoused by the early Theosophical teachers. This process of transmutation and Wood’s dedication to her mastery of luster glazes through a repeated process of trial and error is reminiscent of that of the early Alchemists in their quest to produce gold.

Beatrice Wood, Gold Luster Bowl with 12 Gold Luster Figures (1985), Permanent Collection: Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts / Happy Valley Foundation

“Exploration of luster glazes date back to Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt and they were of great interest to the Alchemists,” says Kevin Wallace, Director of the Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts in Ojai. Alchemy was the Medieval forerunner of chemistry and was concerned with the transformation of matter, particularly converting base metals into gold. According to Wallace, alchemy was also concerned with the perfection of the human body and soul, an alchemical magnum opus or achievement of gnosis. Coincidently, it comes as no surprise that another popular Theosophical text by Besant is entitled, “Spiritual Alchemy.” Just as Wood’s experimentation with luster glazes was a life-long study, so was her thirst for spiritual knowledge and her quest to become a more self-realized, compassionate human being was an ever evolving process.

It can be argued that Wood believed her handmade vessels, themselves, were a physical manifestation of her own thoughts and forms transmuted through her hands into her work. Also inherent in the concept of "thought forms" was the agency of the individual in creating these forms through the vibrations of their thoughts. Likewise, Wood believed that the artist sends out similar vibrations through the creation of his or her works. In her autobiography, she writes “there is a vibration around things made with the hands and love that no machine can copy.” In understanding her work in this way, it only makes sense that she sought the purest and finest of glazes for these vessels, seeking to represent these manifestations of her consciousness in the highest manner.

In an article for The Star, Wood writes “It is truly marvelous to create, for thus we touch divinity…we can (...) reveal art by the intensity of our understanding and by the power of our emotions. Art and beauty are imperative for spiritual development. Art helps man to soar to the higher consciousness, to touch the world of the spirit rather than the world of matter.”

Interestingly enough, Wood's study of Theosophy is also partially responsible for her discovery of luster glazes and her own interest in ceramics. For it was during a trip to the Netherlands to hear Krishnamurti speak that Wood discovered and purchased her very first set of luster-glazed ceramics, a set of six plates, which fascinated her so much that she was inspired to create a matching teapot and enroll in her first ceramics class upon returning home in 1933.

Wood’s work is in the permanent collections of the Los Angeles County Art Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, and the Victoria and Albert Museum among others.

The Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts in Ojai, California is a center celebrating and preserving the legacy of the contemporary artist. Open to the public, it houses her studio, permanent collection of her work, personal library and vast collection of folk art.