Review: It’s Much Louder Than Before at Anat Ebgi

Constance Tenvik, Supernature, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Anat Ebgi. Artwork image by Mason Kuehler.

Over the course of the pandemic, society has been usurped and spun into an interpolating web of the unknown. March 2020 marked the beginning of a broad range of cancelled plans, surreal periods of quarantine, and the grief we reconcile as a collective world today. Tucked away into the peripheries of this extraordinary change has been the abrupt refashioning of queer nightlife, the communities that thrive in esprit de corps through underground subcultures, and a bubbling excitement that yearns to dance the night way and celebrate resilience. It’s Much Louder Than Before, organized by James Bartolacci and Stefano di Paola, inexplicably lies at the taut deliberations between the adaptability and reconciliation of a party world of yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

Featuring 19 local and international artists, primarily based in California and New York, It’s Much Louder Than Before showcases a multi-disciplinary body of work including ceramics, painting, photography, and mixed-media installation. Imbued within the exhibition is a keen focus on representing the diverse spectrum that embodies the queer community as seen in Brea Weinreb’s painting titled Mademoiselles of Gay Beach (San Francisco Pride 2018), 2021. Weinreb references photos taken at gay pride in San Francisco while probing divisions of gender and female accessibility in a predominantly male culture. Gender is significantly heightened through hyper-feminine and hyper-masculine initiatives that can be viewed as reenactments of traditional heteronormative cis-gender roles. Constance Tenvik’s Supernature, 2021 is a magnificent party painting that recalls the work of Nikki de Saint-Phalle and James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry Into Brussels,1889. Inspired by literary figures and lesbian bar scenes, Tenvik preserves clandestine female-centric nocturnal economies that are disappearing today.

Anthony Peyton Young, In the Heat of the Night, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Anat Ebgi. Artwork image by Mason Kuehler.

When deciphering the contextual proponents exhibited in this assembly of work, a clear connection is the desire and willpower to document the experiences shared with one another. Christoper Udemezue’s Untitled (Taken by the Loa with a knife in her hand…), 2017 is a consciously staged photograph that investigates spirituality and black liberation. An exploration into nighttime ceremonial voodoo rituals sheds light on trans lives that have little historical documentation. Furthermore, Anthony Peyton Young’s In the Heat of the Night, 2021, evinces a sentimentality through recreated post-nightclub moments that redefine masculinity. Emblazoned with patriotic stars and cowboy paraphernalia, two nude figures intimately pose together that recalls Frida Kahlo’s Two Nudes in the Forest (The Earth Itself), 1939. Robert Andy Coombs’ series of photographs also portrays a human closeness. His work is determined to humanize sexual fantasies of the disabled and fetish communities. By interacting with able-bodied men, Coombs amplifies the ambivalent tensions at the center of societal misconception to provide the viewer with an introspective lens. Coombs celebrates the vessel in which he inhabits by autonomously reshaping and transforming queer archetypes.

Documentation and participation often go hand in hand. Matthew Leifheit’s They Live by Night, 2019, documents a history that is at a cultural loss due to assimilation. Images of the “meat pack” Fire Island cruising scene photographed at night serve as an archive of generational change. Each small-scale image is taken with a long exposure without flash that generates an extraordinary dimensional quality. Visibly outlined in DeSe Escobar’s Serenity and Shade, 2015, are the marks and stories in a thrifted dress that collectively memorialize “the night out.” Escobar has been a devoted practitioner in New York City’s rave culture by hosting and promoting a network of events that act as safe places of expression for the queer community. Her work functions as an archival performance piece of a scene that existed in the city’s warehouses before heavy policing became an eminent obstruction.

The disappearance of safe spaces to road-test identity has forced a generational divide and generated a new version of queer isolationism. In Alannah Farrell’s 2nd Avenue Fantasy (The Cock), 2021, the artist commemorates an after hours scene in which various characters spaced intentionally apart from one another are lost within the spectacle of their own worlds. Farrell’s painting interrogates the constantly changing topography of familiar, emotive, and physical space. Furthermore, Farrell persuades the viewer to consider the onslaught of nightclub venue pandemic-related closures that have taken a great toll on the index of available areas for improvisatory expression.

In the private and public space, anxiety has been significantly heightened by a constantly shifting social sphere. Although Paulson Lee’s The Hills, 2019, is alluringly enigmatic, it also questions uneasy moments of tension. Amidst a modernist Hollywood Hills backdrop, a vibrant figure pauses mid-phone call to survey the scene. Lee investigates coded gender roles while also dissecting the mythologies manufactured by a Freudian digital landscape. His fascination obliges the audience to reckon with a digital universe that has been the sole open space to maintain social relationships. Moreover, James Bartolacci also makes use of digital media to engage and archive his communal sphere. In Junlin and Their Handmade Top, 2021, Bartolacci depicts his protagonist in a ruminative state on a makeshift bed next to poppers and a phone. Displaying a strong interiority through pastel, the artist prompts a moment for self-reflection while questioning the human need to remain connected.

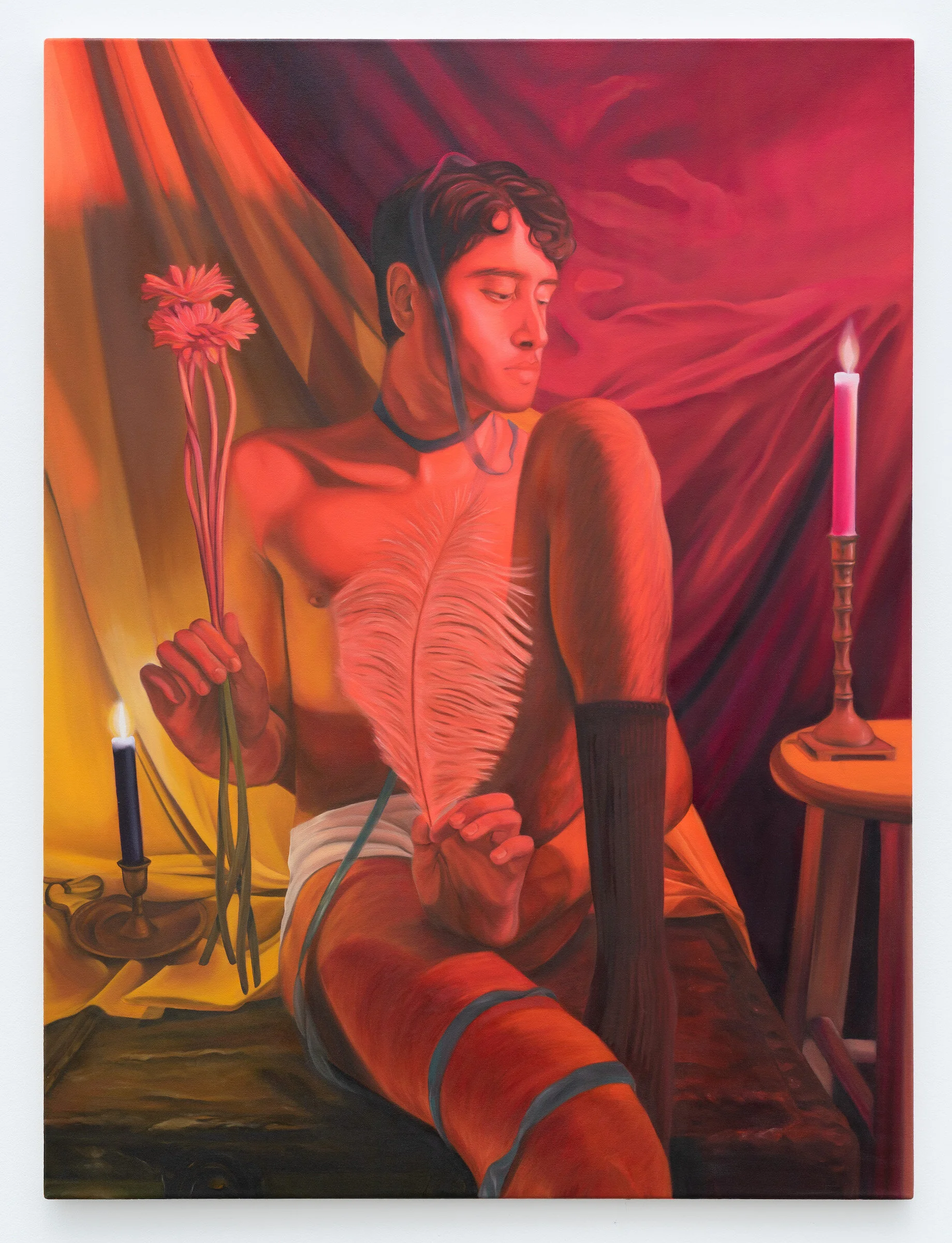

Shahin Sharafaldin, Nicholas in the Belvedere, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Anat Ebgi. Artwork image by Mason Kuehler.

Portraiture is amongst the oldest artistic forms of documentation ensconced in queer history. From the many busts of Antinous and Hadrian to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Portrait of Oscar Wilde, 1895; portraits have acted as a cardinal form of historical preservation. Inviting the viewer with a thespian gentility, Shahin Sharafaldin’s Nicholas in the Belvedere, 2021, uses portraiture to cultivate an intimate humanity with his subject. He effortlessly plays with two candlelights to generate a tenderhearted color temperature. Red undertones animate delicate hair follicles and kindle a perceptual warmth, while the protagonist poses with an ostrich feather and gerbera daisies in hand. In continuation, Marcel Alcalá also embraces portraiture in their painting Fierce Drag Jewels (Portrait of Jacob Pollin), 2021. Deploying multiple gender, object, and cultural signifiers, Alcalá pays careful attention to their subject’s individuality. In contrast to one another are the subject’s hairy chest decorated with glamorous jewelry, pharmaceutical objects in close proximity to an N-95 mask, and a Juicy Couture purse with a painted Star of David. Hollywood’s Roosevelt Hotel serves as a bewitching backdrop that is further exalted by a Liberace-esque gold frame that features two cherubs in pliable poses.

Krzysztof Strzelecki, Pool Party, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Anat Ebgi. Artwork image by Mason Kuehler.

Important aspects of representation include an exploration of bodily perception, the movement patterns linking sociological spaces, and the universality of the human sense of belonging. Two “blue dream” male figures affectionately hold each other in Justin Yoon’s Fantasy of Loneliness, 2021. At first glance the men appear coupled together, however they are actually the same person. Playing with a series of characters that act as placeholders for emotional feeling, Yoon explores subconscious nostalgia as a faction point that cannot be revisited. Knead Myself, 2021 by Trevon Latin, is part of a series of polychromatic hand-sewn works that evoke the grandness of Leigh Bowery, Susanne Bartch parties, and Bisa Butler’s vibrant quilting. Loud and pink, Latin anthropomorphizes sequined textures to outline a spate of extrusions that include a high heel, five-fingered hand, and two tentacles. Eyes with buttoned pupils pop out of the surface, suggesting cathartic self-awareness that is animated through the creation of characters. Furthermore, Pool Party, 2021 by Krzysztof Strzelecki generates prismatic body-inclusive gay cruising fantasies on ceramic vessels. The artist also reimagines the rainbow as a symbol of equity to counter its association with fear and homophobia in his native country of Poland. With a Hockney-esque palette of colors, Strzelecki’s world sparks awareness while celebrating pleasure and human delights.

In sum, It’s Much Louder Than Before decisively conveys a full spectrum of the queer community. Spawning a discourse on inclusivity, heterogeneous narratives, and the light and dark sides of nightlife, this group exhibition forces a reckoning and healing of our collective trauma endured during the pandemic. It’s Much Louder Than Before gives prominence to a ubiquitous voice of camaraderie that values resilience. Although pain can be whipped up in moments of struggle, fellowship can lead to a societal metamorphosis that upholds respect, equity, and human compassion.

More information on the exhibition can be found at Anat Ebgi.